Saying ‘Yes’ to Saving Lives

NVOT teachers and staff members advocate and educate students on organ donation

May 13, 2022

Getting a driver’s license is one of the top things high school students look forward to. When the time comes to go to the MVC and make it official, excitement brims as they fill their forms out, anticipating what they will do with their newly earned freedom. But there’s one question at the end that most students haven’t thought about: saying ‘yes’ to being an organ donor.

22 people die each day waiting for an organ transplant, and only 36 percent of New Jerseyans are registered organ donors.

Teachers at NVOT are on a mission to change that.

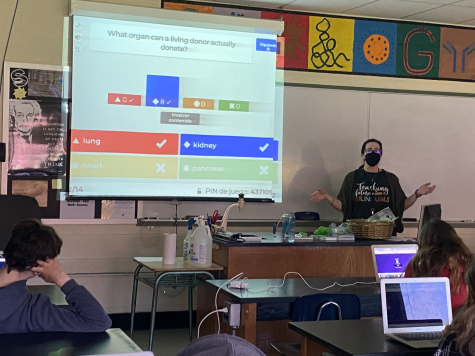

Spanish teacher Lisa Veit is a certified speaker for the non-profit organization New Jersey Sharing Network. For the past twelve years, she has been using her knowledge and experience to spread awareness about organ donation.

“The key reason why I started going into classes was that my father had a liver transplant 29 years ago,” Veit said. Her father originally had a successful transplant, but he needed a new one seven years later. Despite being on the top of the waiting list at “the top hospital in the world,” no organs came through. Over the course of two weeks, ten patients died at the hospital awaiting transplants—Veit’s father was one of them. “Speaking to classes became kind of a way that I processed this death,” she said. “His death and so many other people that I have known that have gone through the same issue.”

Special Education teacher Jodi Ben-Meir’s father was on the waiting list for a heart transplant from August 2004 until May 2005, when he received a call in the middle of the workday to come to the hospital. The transplant was successful, and he “walked [Ben-Meir] down the aisle of [her] wedding 12 days later.”

Like Veit, Ben-Meir saw how sharing her experience can make people more open to organ donation: “There are a lot of people in my family and friends who after that decided to become organ donors or at least get on the list because they saw pretty much the impact of how it can change the lives of families.”

During the years following her father’s transplant, Ben-Meir has been attempting to disprove myths and stigmas around organ donation, primarily the idea that doctors would prioritize saving organs over saving lives in the case of something like a car accident. “I know it’s not true at all, especially having family in the medical field. It’s not true,” said Ben-Meir.

NVOT Nurse Virginia Ferencevych’s daughter is currently being evaluated for the organ transplant list. Ferencevych too understands the urgency for organ donors and is hopeful that current students will get involved. She explained that younger generations “are more open to things”; they have “a different outlook on life than older people that are kind of set in their ways.”

Still, at present, the need is great. The low number of people signing up to donate is insufficient compared to the high number of people on the list urgently waiting for organs—there are currently 90,000 people in the United States on the waiting list for a donor’s kidney.

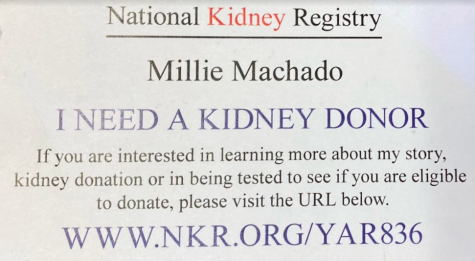

Spanish teacher Mildred Machado is one of those people.

Machado suffers from a hereditary disease known as polycystic kidneys. Machado’s kidney is currently at 18 percent function, which puts her at risk for going on dialysis and the likelihood of stopping what she loves doing most—teaching.

Despite the circumstances, Machado tries to lead a normal life in an effort to keep up her hope. Every day, Machado reassures her family and students with positivity, which is an important yet difficult step in the process. “Like Dr. Sabatini says: ‘control what you can control,’ and there are some things I can’t control, so I’m not going to stress over it,” she said.

Before Machado’s diagnosis and need for a kidney, she was very private about her health and personal life. This changed when her “nephrologist and the team at Hackensack Transplant Center said that you have to advocate and tell people that you need a kidney so I would have more chances of finding a donor.” Machado explained that the process of registering and testing to be a donor is lengthy and precise. “When you register as a donor, the hospital will call you, and then it’s just one whole day of tests because they have to make sure that the person who’s donated is donating as healthy,” she said.

Machado’s and her father’s diagnosis completely changed her life, as she began to realize “how precious life is and how important it is for organ donors and donations.” She created a website in order to further her efforts in receiving a kidney donor.

Her site has had over 1,000 visitors and 19 people have registered as potential donors. On her site, she explains the four types: direct donation, paired exchange donation, Good Samaritan donation, and voucher donation. She also highlights the major parts of the surgery and the possible risks.

Machado emphasizes that all she wants is the opportunity to finally be able to return to normalcy: “The most important thing in life should be your life and to continue living that life, so you can continue giving to others. I just want the gift of life. That’s all I want. And I want the school and my students to share my story.”

All three staff members are working to educate the community by dispelling myths and addressing concerns. They hope to convince more people to become potential donors and to help in this urgent health crisis. Veit shared that her presentations have already made some impact. One of her students told her how his sister chose to be an organ donor: “I was at your presentation and my sister got her license, and I told my whole family. And so when I drive, I’m gonna check off that box too.”