I hate mosquitoes. I’m the person who’d always get the most mosquito bites in my family, so I went into this summer not expecting anything different. I thought just a few spritzes of mosquito repellent whenever I went hiking or stayed outside for more than ten minutes would suffice.

But then I would find bites after taking my dog to go to the bathroom outside (1-2 minutes), going into the car (several seconds), and watering the plants (2-3 minutes). I wasn’t even safe indoors—I’d be watching a movie in my living room and would find multiple bites peppering my skin after the credits rolled. And it was always in the most inconvenient places (right where the side of sneakers would rub against my ankles, all the areas that would touch my bed or chair whenever I tried to relax, or even on my face).

Why were they biting me? Why were there so many of them? Why am I getting so many more bites this summer than every other one in my life? All of these questions led me to writing this article, a rant and a deep dive into whether the mosquito population has increased and what we can do about it.

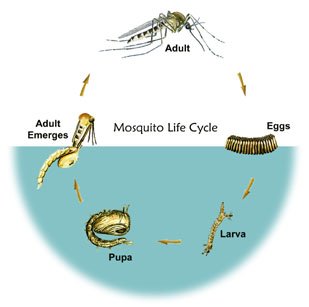

To start off, we have to know why mosquitoes bite. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), female mosquitoes bite people and animals for their blood to help in the production of eggs, with the itching and swelling being a result of their saliva. In order to collect the blood, they use six specialized needles hidden in their proboscis to break through the skin, which can be seen in this video by PBS Digital Studios.

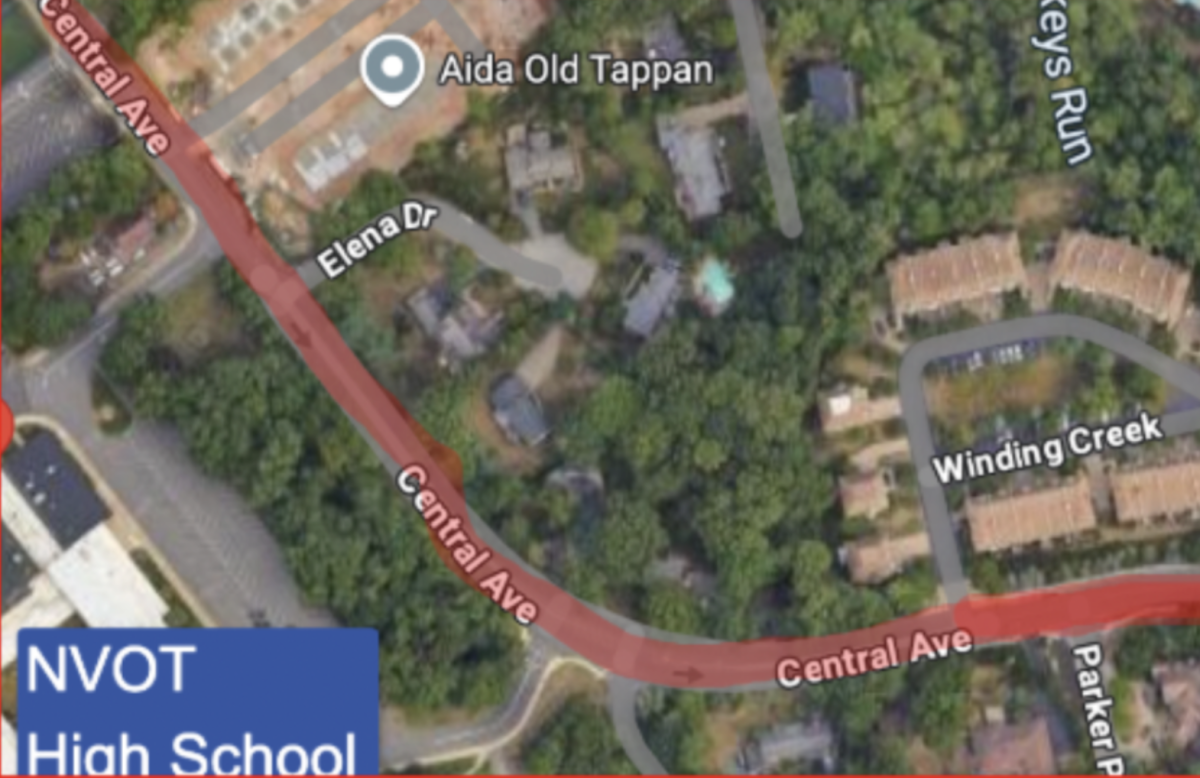

Mosquitoes are widespread across New Jersey. Rutgers University’s Center for Vector Biology recorded 63 of mosquito species and by looking at their mosquito species distribution report, most of them inhabit the entire state such as Aedes albopictus (tiger mosquito), Aedes canadensis (woodland pool mosquito), and Culex pipiens (common house mosquito).

So how could these populations increase? The answer, like most things nowadays, is climate change. Mosquito populations are affected heavily by temperature. According to Bite Back, a pest control company operating in New Jersey, mosquitoes are active in temperatures “above 50ºF” and when winter comes, many species die and let their eggs freeze in water, but some hibernate “until the weather gets warmer.” As weather grows warmer and warmer and winters grow shorter and shorter, mosquito populations will be able to grow.

Populations are also influenced by rainfall and human activity. Bite Back states that mosquito eggs can be laid in “at least an inch of water,” allowing their eggs to be laid in virtually any form of standing water. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), mosquito eggs and larvae need water to hatch and survive, but even if their supply of water evaporates, eggs can “survive dry conditions for a few months.” This resiliency allows them to lay their eggs in things as simple as the inside of tire swings and litter, making our man made world the perfect place to spread.

In an interview with Stanford University’s news website Stanford Report, Desiree LaBeaud, professor of pediatrics at Stanford Medicine, said, “Everything we’re doing as we alter our world puts us more at risk: They breed in the plastic waste we discard; they thrive in urban environments, and they like it hot. They’re also fairly sneaky. It’s hard to find them when they’re resting, so you don’t know where to spray.”

However, an article published by North Jersey news May 2024, predicted that the mosquito population would decrease as a result of New Jersey facing “less rainfall than normal.” Though they admitted that predicting rain can be unreliable at times, it’s clear that their prediction was wrong and the population of mosquitoes in general has increased.

According to Erin Mordecai, associate professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University, the population of virus transmitting Aedes mosquitoes has been exponentially growing “in the last 30 years” (StanfordReport).

This brings us to why mosquito populations rising isn’t just annoying, but also a health risk. Throughout the United States and the world, wherever mosquito populations grew, so did the cases for malaria, dengue fever, West Nile virus, and other mosquito-borne illnesses (StanfordReport). The spread happens when a mosquito bites an infected person or animal, becomes infected itself, and spreads the sickness as it bites more people (CDC). Although infected people don’t always get sick, mosquito-borne illnesses are still a serious issue. LaBeaud said, “We’re also much less prepared for the diseases they spread, particularly dengue, than we are for malaria” (StanfordReport).

So what can be done?

It’s impossible to eradicate all mosquitoes, especially when they’re a crucial part of the environment. Instead, simple eco-friendly methods to reduce their population or avoid being bitten can be made, such as naturally reducing the population with genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes.

GM mosquitoes, specifically Aedes aegypti, are regulated and approved by the EPA and have been released in places like Texas, Florida, Brazil, the Cayman Islands, and India. According to the CDC, the GM mosquitoes pose no threat to the environment or people and are simply mosquitoes with “a self-limiting gene” and “fluorescent marker gene.” The idea for GM mosquitoes is that after they’re approved by an area’s local authorities, they’ll be mass-produced in a lab, released into the wild to mate with wild mosquitoes, spread the self-limiting gene, eventually decrease the overall population, and slow the spread of future diseases. The CDC states that GM mosquitoes have been successful and “over 1 billion mosquitoes have been released” since 2019.

Despite the positive results, GM mosquitoes haven’t been released in New Jersey yet. Smaller steps can be taken to prevent bug bites instead. For example, since mosquitoes need a lot of moisture and water to survive and reproduce, Arrow, a New Jersey based pest control company recommends that people “control stagnant water sources” in areas ranging from the gutters, bird baths, and even tire swings and be aware of vegetation, where they might hide throughout the day. The CDC also recommends that people use EPA-registered repellents, wear long or thick clothes, and treat the wound with ice or a baking soda and water mixture (recipe provided here).

While this isn’t perfect, and mosquitoes may still follow you into your car or home, hopefully it can help prevent more bites next summer.